In March 2022, a study published in Nature Cancer highlighted Cadherin 17 (CDH17) as an ideal target for chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy in gastrointestinal tumors (including gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer, and colorectal cancer) and neuroendocrine tumors (NETs). CDH17 swiftly gained attention across major news platforms, providing fresh insights into tumor-associated antigens and the development of safe immunotherapies for solid tumors. Now, after two years, let’s explore the current landscape of immune therapies targeting the CDH17 pathway. But first, let’s delve into the fundamental aspects of CDH17.

1. The structure of CDH17

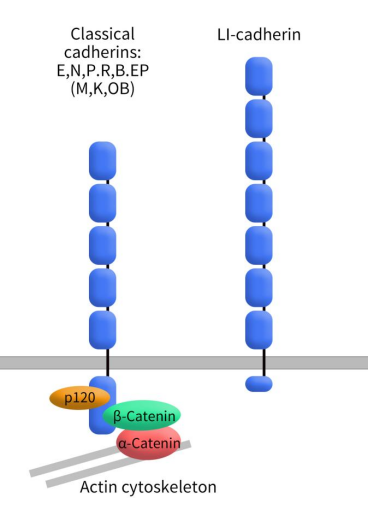

Cadherin-17 (CDH17), also known as liver-intestine cadherin (LI-cadherin) or human peptide transporter-1 (HPT-1), is a structurally unique member within the cadherin superfamily. Cadherins constitute a superfamily of cell adhesion molecules that rely on Ca2+ and belong to the type I transmembrane protein family. They are all single-pass transmembrane proteins, with their N-terminus located extracellularly. The extracellular domain of cadherins typically consists of multiple repeats, each composed of approximately 110 amino acid modules, collectively referred to as the cadherin extracellular domain (EC). Within this domain, several cadherin-specific motifs are present. Classical cadherins, such as E-cadherin (CDH1), N-cadherin (CDH2), and P-cadherin (CDH3), contain five EC domains in their extracellular region. Their intracellular domain consists of 150-160 amino acids and remains highly conserved.

Unlike classical cadherins, CDH17 belongs to the 7D-cadherin family. It consists of three parts, including seven extracellular EC repeat domains, a single transmembrane domain and a short cytoplasmic tail. CDH17’s EC1 and EC2 domains originate from EC5 repeats. Notably, CDH17 contains an RGD motif within its EC6 domain, crucial for interactions with α2β1 integrin and activation of integrin signaling pathways in cancer cells. Another significant difference between CDH17 and classical cadherins lies in the extremely short cytoplasmic domain of CDH17 (20 amino acids), contrasting with the highly conserved cytoplasmic regions (150 amino acids) found in classical cadherins or other cadherin subfamilies. Importantly, CDH17 lacks a recognizable binding site for β-catenin, which is essential for interactions with catenins and cytoskeletal components [3] [4].

Figure 1. The structure of Classical cadherins and cadherin-17

The classical cadherin-catenin complex regulates cell adhesion by interacting with intracellular catenins. Although the cytoplasmic domain of CDH17 is short, it also plays a crucial role in cell adhesion processes. Research suggests that the extracellular portion of CDH17 may independently regulate cell adhesion functions. Unlike other cadherins, CDH17 does not seem to act through binding with catenins during cell adhesion; instead, it may directly adhere to cell scaffolding. However, the precise mechanisms of its action remain unclear and require further investigation.

2. CDH17 Distribution and Clinical Significance

CDH17, initially discovered in rat liver and intestines, is also referred to as liver-intestine cadherin. In humans, CDH17’s distribution is primarily limited to the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, colon, and certain pancreatic ducts. It is rarely detected in healthy adult liver, kidney, and heart tissues [5]. Within intestinal epithelium, CDH17 predominantly localizes to lateral and basolateral membranes. Interestingly, CDH17 is aberrantly expressed on the surface of tumor cells, similar to Claudin18.2 and other specific targets. Research findings indicate that CDH17 exhibits varying degrees of expression in gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, bile duct cancer, pancreatic cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Moreover, high CDH17 expression correlates with shorter survival and disease progression in gastric and colorectal cancer patients. CDH17’s differential expression profile makes it an attractive target for novel drug candidates, especially those with enhanced effector function, such as antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), T cell- and NK cell-redirecting antibodies, and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells.

3. CDH17 Mechanisms in Tumors

While the precise mechanisms underlying CDH17’s role in cancer remain elusive, several research studies have shed light on its potential functions.

In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), John Luk and colleagues observed upregulated expression of CDH17 adhesion molecules. In mouse models, CDH17 could transform pre-cancerous liver progenitor cells into liver cancer. Silencing CDH17 using siRNA inhibited both in vitro and in vivo proliferation of primary and highly metastatic HCC cell lines. The antitumor mechanism involves Wnt signaling pathway inactivation, leading to β-catenin relocalization within the cytoplasm. This process is accompanied by reduced cyclin D1 expression and increased retinoblastoma susceptibility [6]. Subsequently, Felix H. Shek’s experiments confirmed SPINK1 as a downstream effector of the CDH17/β-catenin signaling axis in HCC [7].

In gastric cancer (GC), Karl-F. Becke and colleagues identified abnormal CDH17 splicing variants, particularly those with exon 8 or exon 9 deletions, as dominant [8]. Jin Wang and team validated that the downregulation of CDH17 not only suppressed proliferation, adhesion, and invasion capabilities of MKN-45 gastric cancer cells but also induced cell cycle arrest. Additionally, the NFκB signaling pathway was inactivated, resulting in decreased downstream proteins such as VEGF-C and MMP-9. Silencing CDH17 significantly inhibited in vivo tumor growth and was associated with the absence of lymph node metastasis in CDH17-deficient mice [9].

In colon cancer, CDH17 has been shown to interact with α2β1 integrin. It plays a critical role in regulating cell adhesion and proliferation through α2β1 integrin activity. Furthermore, CDH17 promotes the acquisition of liver metastasis by colorectal cancer cells. In summary, CDH17’s multifaceted roles in different cancers underscore its potential as a therapeutic target, warranting further investigation.

4. Clinical Research Progress on CDH17 Targeted Therapy

Cadherin-17 (CDH17) is a non-classical cadherin protein primarily expressed in healthy intestinal epithelium but abnormally overexpressed in various gastrointestinal (GI) cancers, making it a highly tumor-specific therapeutic target. Current CDH17-targeted strategies include antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), cellular therapies (CAR-T/CAR-NK), and other antibody-based or fusion protein approaches.

4.1 CDH17 Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs)

ADCs are currently the industry’s main focus for CDH17-targeted therapies, representing roughly 50% of all investigational CDH17 drugs. Nearly all CDH17 candidates entering clinical development are ADCs, which combine a CDH17-specific antibody with a cytotoxic payload to deliver treatment directly to tumor cells, maximizing efficacy while minimizing off-target toxicity. Key CDH17 ADCs with notable clinical progress in 2025 include:

- HS-20110 | Hansoh Pharma | Phase I

HS-20110 is a CDH17 ADC composed of a humanized antibody linked to a topoisomerase inhibitor, targeting advanced solid tumors, particularly colorectal cancer. In October 2025, Hansoh exclusively licensed global rights (outside Greater China) to Roche, receiving $80M upfront and up to $1.45B in milestones and royalties. HS-20110 is currently in Phase I trials in China and the U.S., evaluating safety, tolerability, and preliminary efficacy.

- 7MW4911 | Mabwell Biotech | Phase I/II

7MW4911 is a CDH17 ADC combining a high-specificity CDH17 antibody with a cleavable linker and a proprietary topoisomerase I inhibitor (MF-6), designed to overcome multi-drug resistance in GI tumors. Approved for IND in China and the U.S. in August 2025, it has begun Phase I/II trials assessing safety, pharmacokinetics, and preliminary efficacy. Preclinical data published in Cell Reports Medicine show potent anti-tumor activity.

- CM518D1 | Keymed Biosciences | Phase I/II

CM518D1 selectively delivers cytotoxic payloads to CDH17-high tumors, including colorectal cancer. NMPA-approved IND in April 2025 enabled multicenter Phase I/II trials in China. Clinical studies focus on dose escalation, safety, and preliminary efficacy.

- HDM2017 | Huadong Medicine | Phase I

HDM2017 is a CDH17 ADC targeting colorectal, gastric, and pancreatic cancers. IND approvals in China and the U.S. allowed Phase I trials to start in 2025, with the first patient dosed in November 2025.

- MRG007 | Lepu Biopharma | Phase I/II

MRG007 is a CDH17 ADC targeting GI tumors. Lepu licensed global rights (outside Greater China) to ArriVent BioPharma, receiving $47M upfront and up to $1.16B in milestones and royalties. IND approval in China (June 2025) and U.S. (November 2025) enabled Phase I clinical trials.

- YL217 | MediLink Therapeutics | Phase I

YL217, developed using the TMALIN® platform, targets CDH17-high GI tumors. IND approvals in the U.S. and China allowed Phase I trials to start globally, with first dosing completed in China in July 2025.

- SOT109 | SOTIO Biotech | Preclinical

SOT109 employs Synaffix GlycoConnect®/SYNtecan E™ technology with exatecan payload, showing strong anti-tumor activity and tolerability in xenograft models. Preclinical/IND preparation is ongoing with plans for Phase I in 2026.

- BR-116 | BioRay Biopharmaceutical | Preclinical

BR-116 is a dual-payload ADC, combining a CDH17 antagonist and topoisomerase I inhibitor on one antibody. Preclinical data in 2025 show promising efficacy and safety, with IND filing planned the same year.

- Other CDH17 ADCs

Multiple CDH17 ADC programs are advancing globally, including DB-1324, LM-350, SIM-0609, AMT-676, TORL-3-600, and ARB series candidates, spanning Phase I/II and preclinical stages. VelaVigo’s VBC108 is a dual-target ADC against CDH17 and CLDN18.2, first-in-class (FIC) globally, showing strong preclinical efficacy and safety with planned clinical trials in 2025–2026.

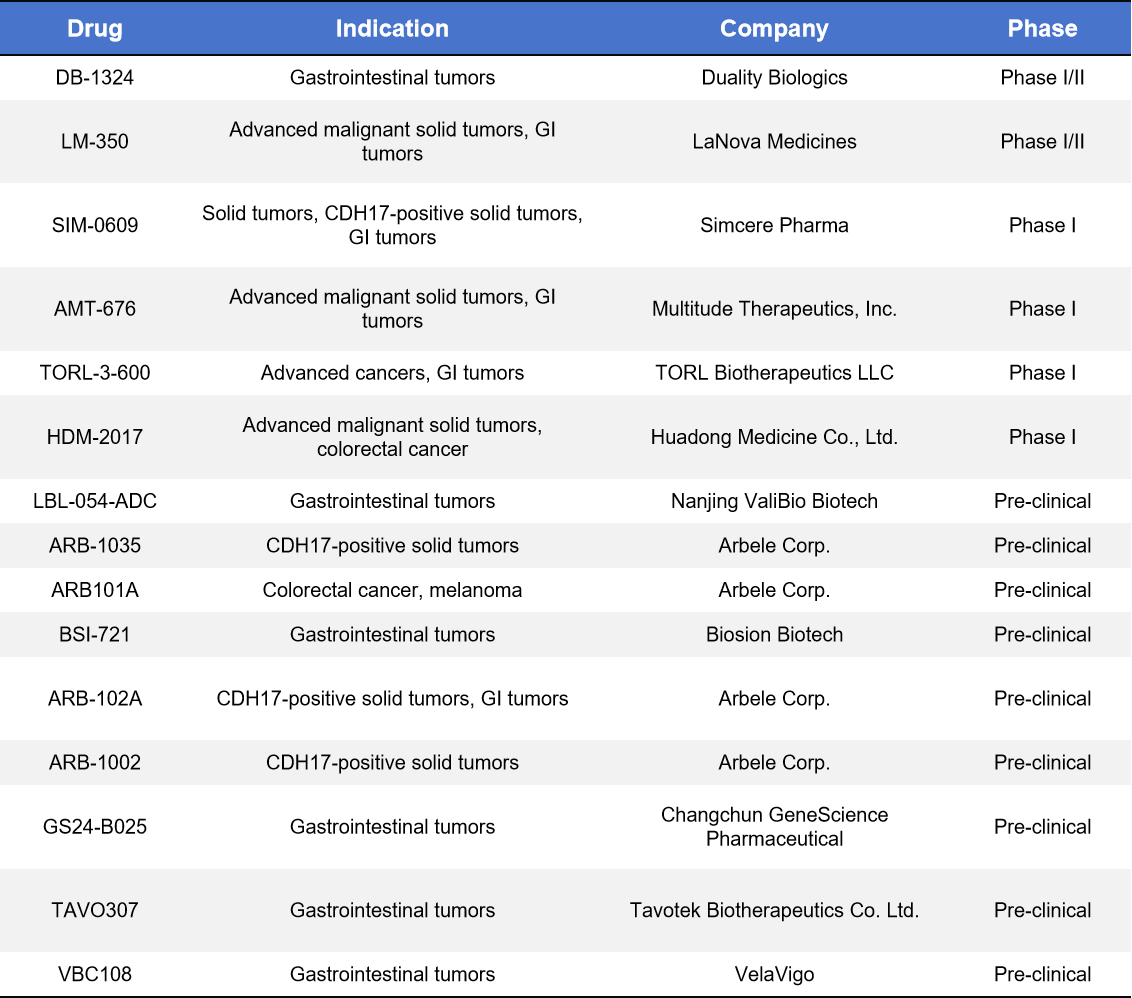

Table 1. CDH17_ADC

CDH17 ADC development is characterized by a China-led innovation + global collaboration pattern.

4.2 Monoclonal, Bispecific, and Trispecific CDH17 Antibodies

Clinical-stage CDH17 antibodies are mainly bispecific, while most other candidates remain in preclinical development.

- Cabotamig | Arbele Corp. | Phase I

A bispecific T-cell engager (CDH17xCD3), recruiting T cells to CDH17-high tumors. First-in-class immune therapy, in Phase I dose-escalation trials for advanced GI cancers.

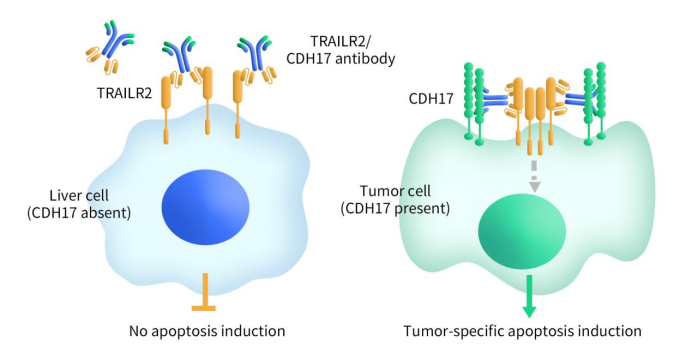

- BI-905711 | Boehringer Ingelheim | Phase I

A tetravalent bispecific antibody targeting TRAILR2 and CDH17, promoting selective apoptosis in CDH17-high tumors while minimizing liver toxicity. In Phase I since 2020, showing preliminary safety and disease control signals.

Other preclinical antibodies include single-, bi-, and tri-specific constructs for CDH17 targeting, mainly designed to enhance ADC delivery or CAR-T recognition.

Figure 2. The mechanism of BI-905711

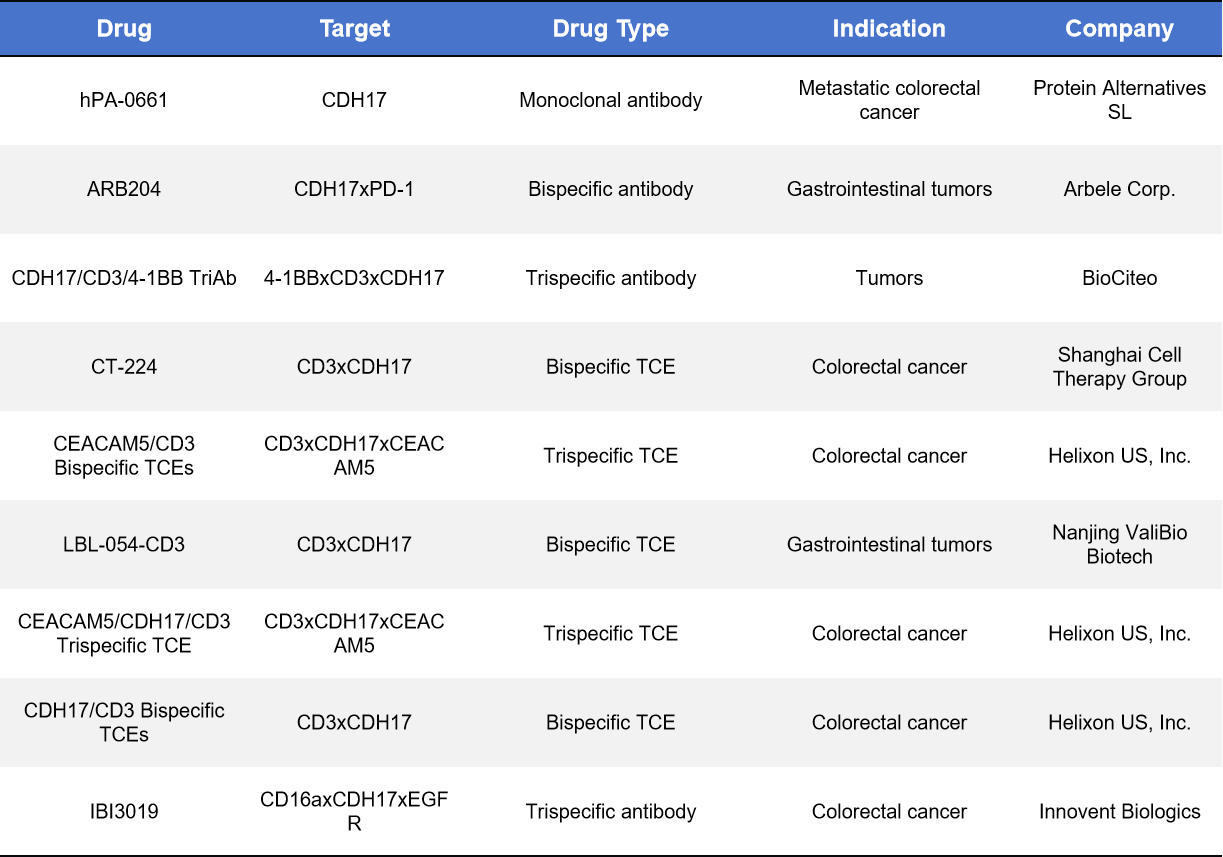

Table 2. CDH17_Monoclonal, Bispecific, and Trispecific

*TCE: Bispecific T-cell engager

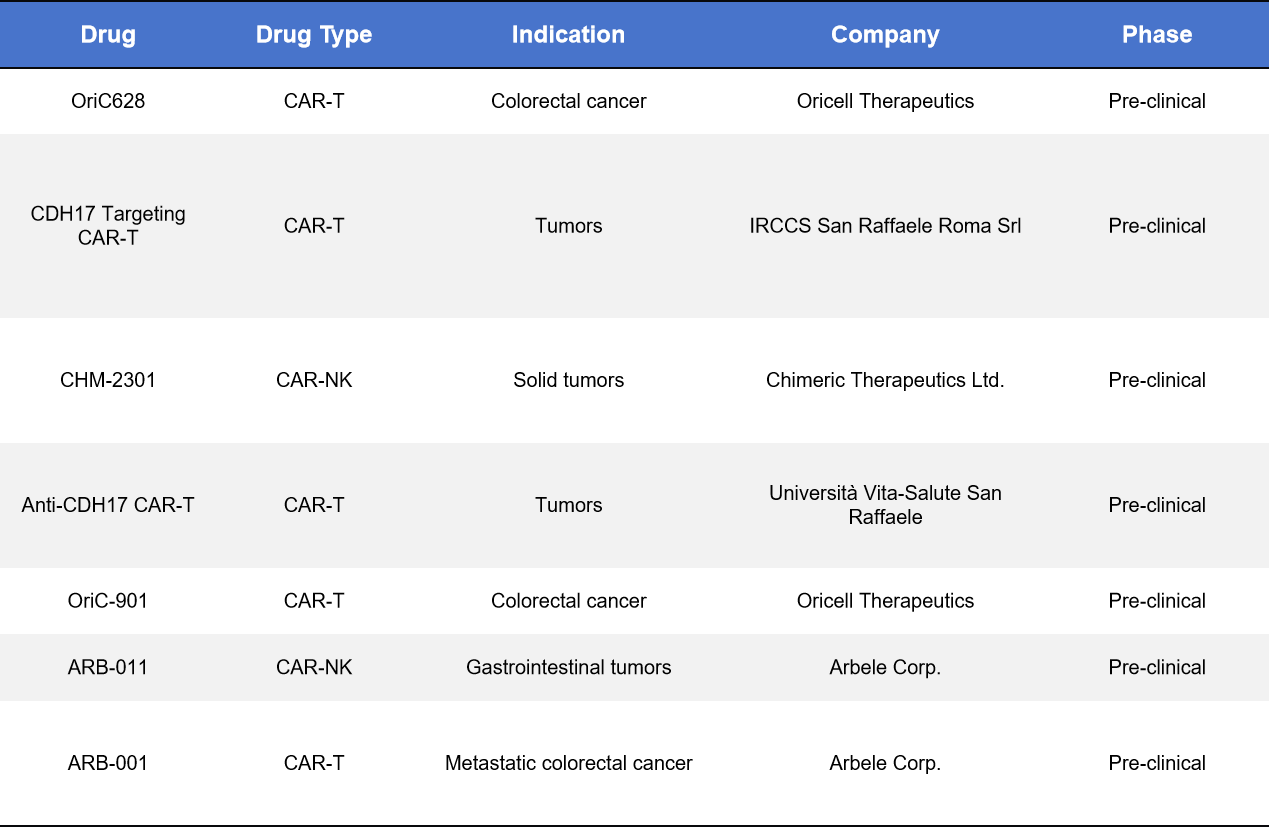

4.3. CDH17 Cellular Therapies (CAR-T / CAR-NK)

CDH17 CAR-T and CAR-NK therapies are in preclinical development, with key players including YuanQi Biotech, Arbele Corp., and Chimeric Therapeutics. These therapies target colorectal and gastric cancers with liver metastases. Challenges include:

- Tumor microenvironment immunosuppression and antigen heterogeneity, reducing efficacy.

- Potential off-tumor toxicity in normal intestinal tissue expressing CDH17.

Current preclinical models show clear tumor clearance and potential synergy with PD-1 inhibitors. Notable preclinical candidates include OriC628, CDH17-targeting CAR-Ts, CHM-2301 (CAR-NK), and ARB-011 (CAR-NK).

Table 3. CDH17_CAR-T/ CAR-NK

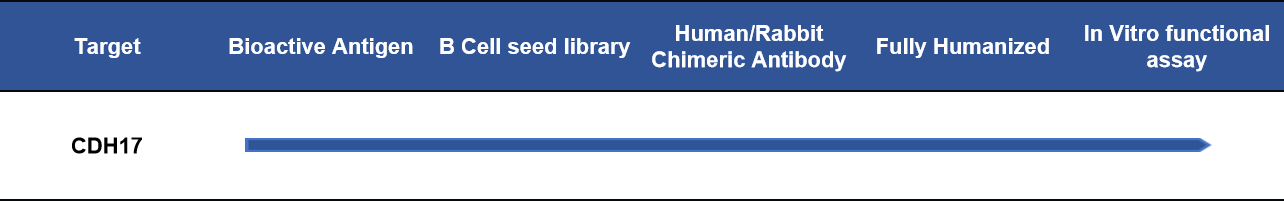

5. DIMA Biotech: Advancing CDH17 Biotherapy Development

DIMA Biotech is a biotechnology company dedicated to preclinical research and development of products and services for potential drug targets. DIMA now offers a full range of products and services related to the CDH17 target. Our products include active proteins, reference antibodies, and flow cytometry-validated monoclonal antibodies. Our services cover a variety of species-specific antibody customization, antibody humanization, and affinity maturation services.

In addition, to expedite the development of CDH17 biologics, DIMA has prepared a single B-cell seed library for the CDH17 target. With our B cell library, lead antibody molecules can be obtained in as little as 28 days, allowing customers to conduct further functional evaluation and validation. Currently, we have screened 41 lead molecules for CDH17, with 36 verified for cross-reactivity with human and monkey proteins. For some molecules, we are also conducting ADC internalization activity and cytotoxicity validation. For specific data, please feel free to inquire.

- CDH17 Protein and Antibody

| Product Type | Cat. No. | Product Name |

| Recombinant Protein | PME100199 | Human CDH17(567-667) Protein, hFc Tag |

| PME101384 | Human CDH17(567-667) Protein, mFc Tag | |

| PME100801 | Human CDH17 Protein, His Tag | |

| PME-M100098 | Mouse CDH17 Protein, His Tag | |

| PME-C100029 | Cynomolgus CDH17 Protein, His Tag | |

| FC-validated Antibody | DMC100485 | Anti-CDH17 antibody(DMC485); IgG1 Chimeric mAb |

| Reference Antibody | BME100198 | Anti-CDH17(ARB102 biosimilar) mAb |

- Progress on CDH17 Lead mAb Molecules

Reference:

[1] Qiu HB, Zhang LY, Ren C, et al. Targeting CDH17 suppresses tumor progression in gastric cancer by downregulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e56959.

[2] Baumgartner W. Possible roles of LI-Cadherin in the formation and maintenance of the intestinal epithelial barrier. Tissue Barriers. 2013 Jan 1;1(1):e23815.

[3] Koch PJ, Goldschmidt MD, Walsh MJ, et al. Complete amino acid sequence of the epidermal desmoglein precursor polypeptide and identification of a second type of desmoglein gene. Eur J Cell Biol. 1991;55:200–8.

[4] Koch PJ, Walsh MJ, Schmelz M, et al. Identification of desmoglein, a constitutive desmosomal glycoprotein, as a member of the cadherin family of cell adhesion molecules. Eur J Cell Biol. 1990;53:1–12.

[5] Gessner R, Tauber R. Intestinal cell adhesion molecules. Liver-intestine cadherin. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;915:136-43.

[6] Liu LX, Lee NP, Chan VW, et al. Targeting cadherin-17 inactivates Wnt signaling and inhibits tumor growth in liver carcinoma. Hepatology. 2009 Nov;50(5):1453-63.

[7] Shek FH, Luo R, Lam BYH, et al. Serine peptidase inhibitor Kazal type 1 (SPINK1) as novel downstream effector of the cadherin-17/β-catenin axis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 2017 Oct;40(5):443-456.

[8] Karl-F. Becker, Michael J. Atkinson, Ulrike Reich, Hsuan-H. Huang, Hjalmar Nekarda, Jörg R. Siewert, Heinz Hofler, Exon skipping in the E-cadherin gene transcript in metastatic human gastric carcinomas, Human Molecular Genetics, Volume 2, Issue 6, June 1993, Pages 803–804.

[9] Wang J, Kang WM, Yu JC, Liu YQ, Meng QB, Cao ZJ. Cadherin-17 induces tumorigenesis and lymphatic metastasis in gastric cancer through activation of NFκB signaling pathway. Cancer Biol Ther. 2013 Mar;14(3):262-70.