In the fields of endocrinology and autoimmune disease research, one target is returning to the spotlight: the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR, Thyrotropin Receptor). In recent years, therapeutic strategies centered on TSHR have evolved rapidly, ranging from blocking monoclonal antibodies and small-molecule antagonists to novel approaches aimed at modulating pathogenic autoantibodies. Both academia and industry are actively investing in this target. Clinical studies indicate that TSHR-targeting antibodies demonstrate favorable safety profiles and preliminary efficacy in Graves’ disease and thyroid eye disease. At the same time, orally available small-molecule antagonists and inverse agonists offer new possibilities for long-term management. More importantly, emerging research has expanded the functional scope of TSHR to include immunometabolic regulation and thyroid cancer, elevating it from a “hyperthyroidism target” to a multidimensional therapeutic node spanning immunity, metabolism, and oncology.

1. From Structure to Signaling: How TSHR Precisely Regulates Thyroid Function

TSHR is a core component of the thyroid regulatory network. Its unique structural features confer high sensitivity to both endogenous ligands and autoantibodies, while its characteristic tissue distribution underpins its critical role in endocrine homeostasis and autoimmune disease. Through multi-pathway coupling and complex signal transduction mechanisms, TSHR converts hormonal stimulation or aberrant autoantibody signals into diverse cellular responses, serving as a central hub linking structure, physiological function, and disease pathogenesis.

1.1 Structural Features of TSHR: A Typical GPCR—Yet More Than a GPCR

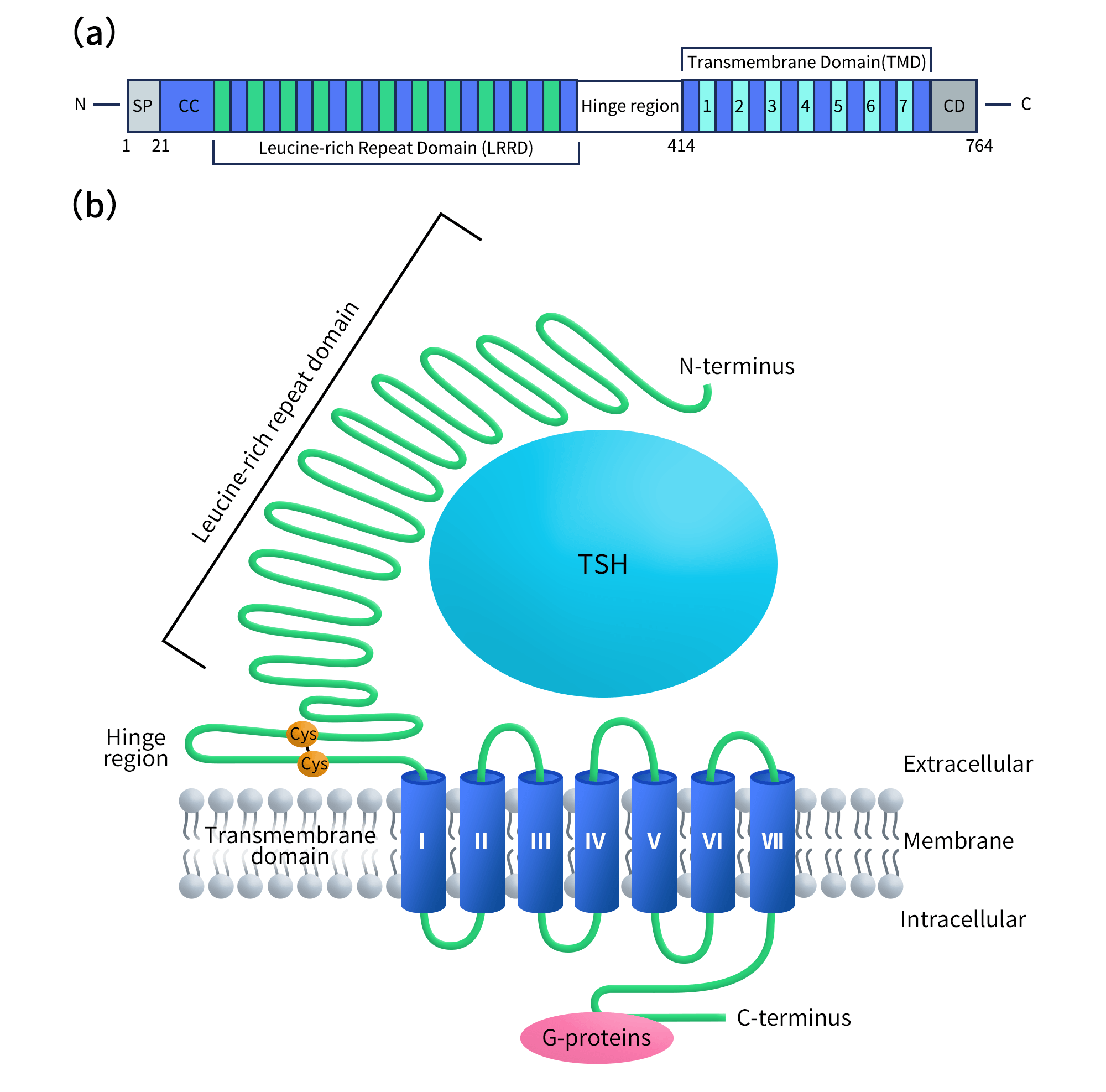

TSHR (thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor) belongs to the glycoprotein hormone receptor family and is a highly specialized G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR). It consists of a large extracellular domain (ECD), a canonical seven-transmembrane (7TM) domain, and an intracellular C-terminal tail. With an overall length exceeding 700 amino acids, TSHR possesses an unusually complex extracellular architecture compared with most GPCRs.

The extracellular region is primarily composed of leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) and a hinge region, which together form the principal binding interface for TSH as well as stimulating antibodies (e.g., M22) and blocking antibodies (e.g., K1-70). This region is also enriched in critical glycosylation sites. The transmembrane domain mediates signal transduction following receptor activation through interactions with G proteins and effector molecules such as β-arrestins [1].

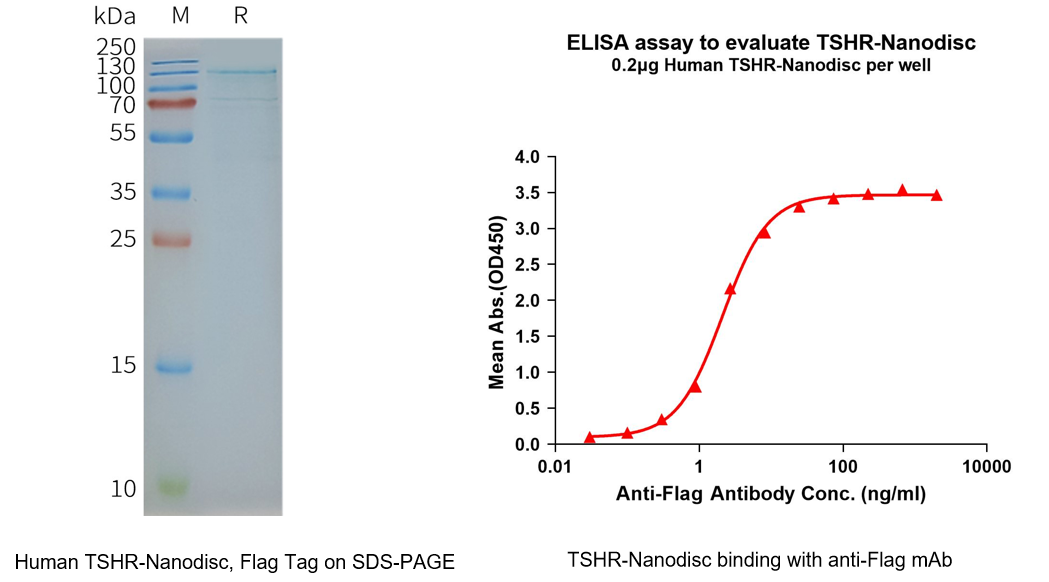

Figure 1. (a) Domain organization of the full-length TSHR protein. (b) The topology model of TSHR.

1.2 Tissue Distribution of TSHR: Beyond the Thyroid to Multiple Peripheral Tissues

TSHR has traditionally been regarded as a thyroid-specific receptor, predominantly expressed in thyroid follicular cells, where it governs thyroid hormone synthesis and secretion. However, accumulating evidence indicates that TSHR expression is not restricted to the thyroid.

In patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy, TSHR expression has been detected in orbital fibroblasts and adipocytes. Activation of TSHR by stimulating autoantibodies in these cells induces adipogenesis, inflammatory responses, and hyaluronan accumulation, leading to the characteristic orbital pathology. In addition, TSHR expression has been reported in immune cells, such as macrophages, where TSHR signaling can influence cellular metabolic states and inflammatory polarization.

Notably, certain thyroid malignancies—particularly differentiated thyroid cancers and radioiodine-refractory tumors—retain TSHR expression, making it a potential therapeutic target in oncology. Collectively, the expanded expression profile of TSHR provides a molecular basis for its involvement in autoimmune disease, inflammation, and cancer.

1.3 Functions and Signaling Pathways of TSHR

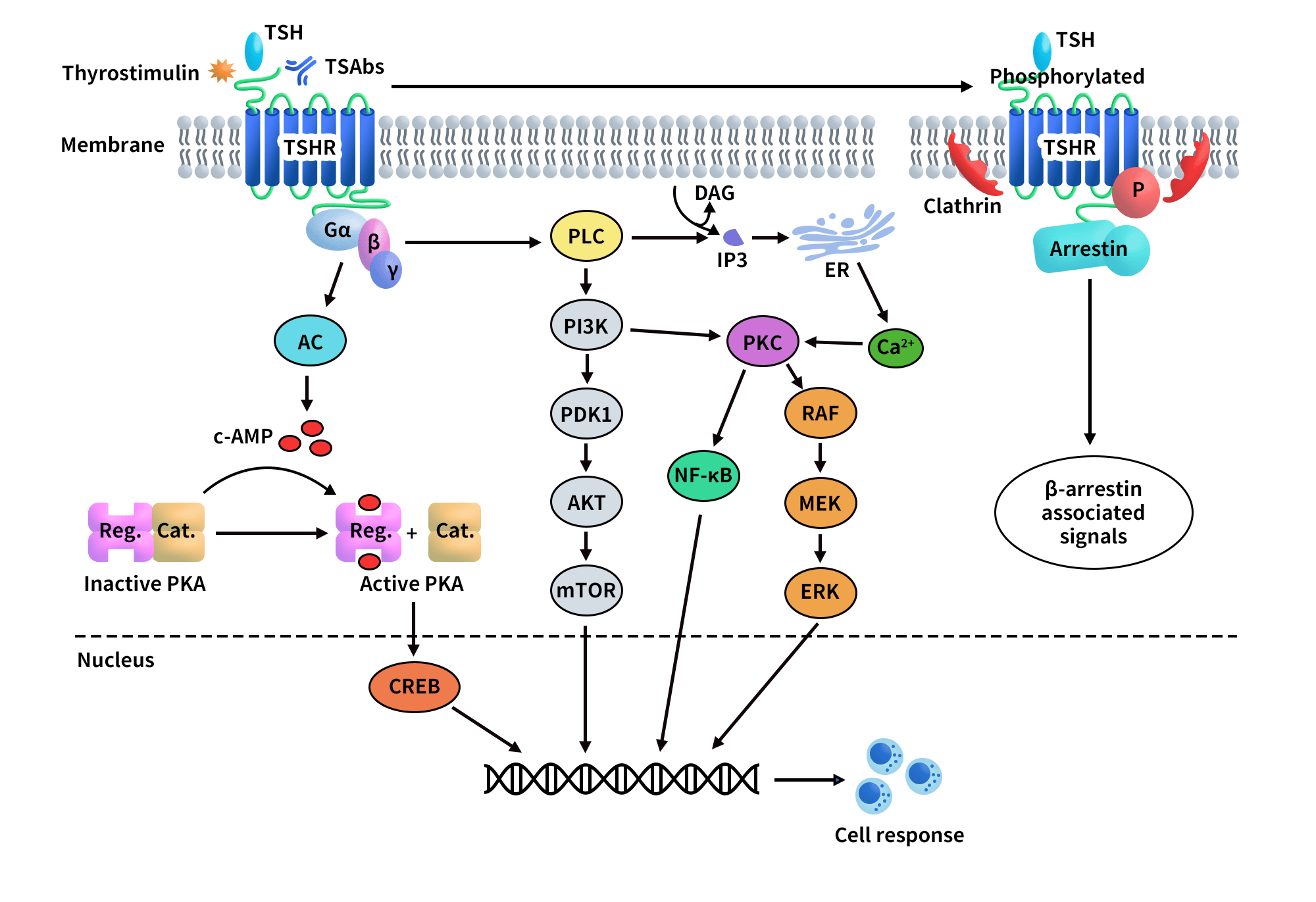

TSHR exhibits highly diverse signaling functions. Its core signaling network encompasses classical hormone-driven regulation, autoantibody-mediated aberrant activation, and crosstalk with other receptors. The most fundamental mechanism involves TSH binding to TSHR, leading to activation of the Gs–cAMP–PKA pathway and promoting the synthesis and secretion of thyroid hormones T3 and T4. This signaling axis is central to normal thyroid physiology [2] and forms the biological basis for pathological hyperactivation.

In autoimmune thyroid diseases, TSHR function is primarily regulated by different classes of autoantibodies. Stimulating antibodies (e.g., M22) bind to the extracellular LRR region and induce a conformational transition of the receptor from an inactive to an active state, thereby initiating transmembrane signaling [3]. In contrast, blocking antibodies (e.g., K1-70) competitively inhibit the actions of TSH or stimulating antibodies, maintaining the receptor in an inactive conformation [4]. Cryo-electron microscopy studies have identified the hinge region as a critical regulatory element governing this conformational switching [5].

At the structural level, the active state of TSHR is closely associated with cholesterol molecules, suggesting preferential localization within cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains. Conformational rearrangements of the transmembrane helices—such as outward movement of TM6 and inward displacement of TM7—are key steps for G protein coupling [5,6].

In Graves’ ophthalmopathy, TSHR can also engage in functional crosstalk with the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R), amplifying inflammatory and adipogenic signaling and constituting a major molecular basis of disease pathogenesis [7,8]. Beyond canonical G protein signaling, TSHR can activate β-arrestin-dependent and other non-classical pathways to regulate hyaluronan synthesis, cellular stress responses, and inflammation [2,9].

Figure 2. TSHR-mediated signaling pathways.

2. Progress in TSHR-Targeted Drug Development

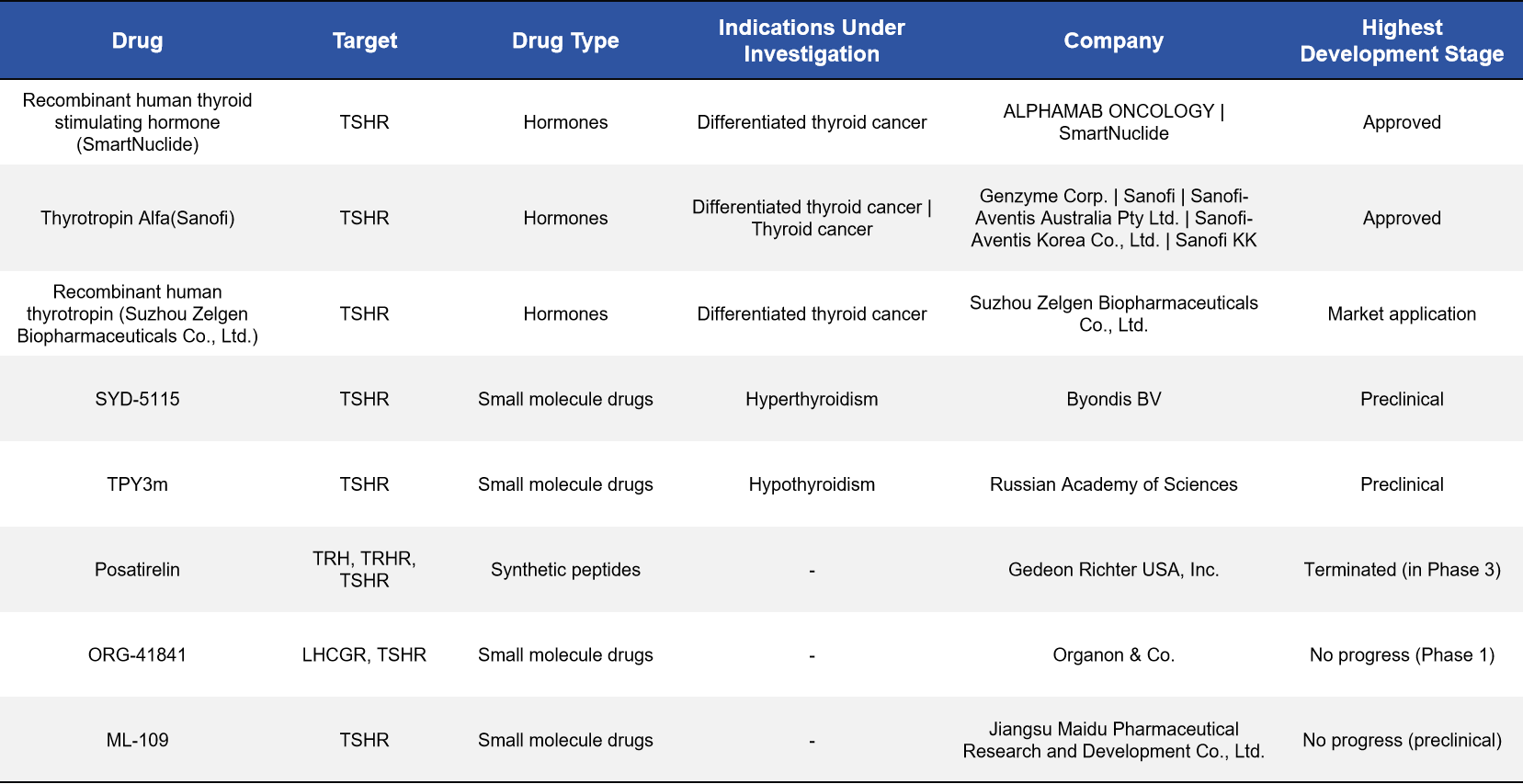

TSHR is a central regulator of thyroid function and a key therapeutic target in thyroid-related diseases. In recent years, drug development efforts targeting TSHR have accelerated markedly, giving rise to an overall landscape characterized by well-established agonists, highly active small-molecule inhibitor programs, and a steady emergence of innovative modalities.

At present, two TSHR agonists have been approved, primarily for use in the diagnosis and adjuvant management of differentiated thyroid cancer. Beyond these, multiple candidates are under clinical investigation, spanning Phase I to Phase II development. Graves’ disease and thyroid eye disease (TED) represent the most intensively pursued indications. Notably, with advances in platform technologies, TSHR is now being explored in CAR-T cell therapy, LYTAC-based degraders, bispecific antibodies, and molecular imaging probes. These novel approaches are largely directed toward complex or refractory conditions—such as treatment-resistant thyroid cancer and severe ophthalmopathy—highlighting the expanding therapeutic potential of the TSHR target.The major drug classes and representative developments are summarized below.

2.1 Agonists: The Most Clinically Mature Therapeutic Class

Agonists represent the most mature and widely applied class of TSHR-targeted agents. By activating TSHR, these drugs enhance radioactive iodine uptake in thyroid cells, thereby improving the accuracy of diagnosis and therapeutic decision-making in differentiated thyroid cancer.

Representative agents include human thyrotropin (SmartNuclide), recombinant human thyrotropin alfa (Sanofi), and recombinant human thyroid-stimulating hormone developed by Zelgen Biopharmaceuticals. Among these, the first two have been approved and used clinically for many years, forming the cornerstone of current clinical applications of the TSHR target.

2.2 Small-Molecule Inhibitors: An Active Development Track for Graves’ Disease

Small-molecule drugs have emerged as one of the most closely watched directions in TSHR drug development, particularly for Graves’ disease and thyroid eye disease. These agents aim to block or modulate TSHR activity, thereby mitigating thyroid dysfunction driven by aberrant immune activation.

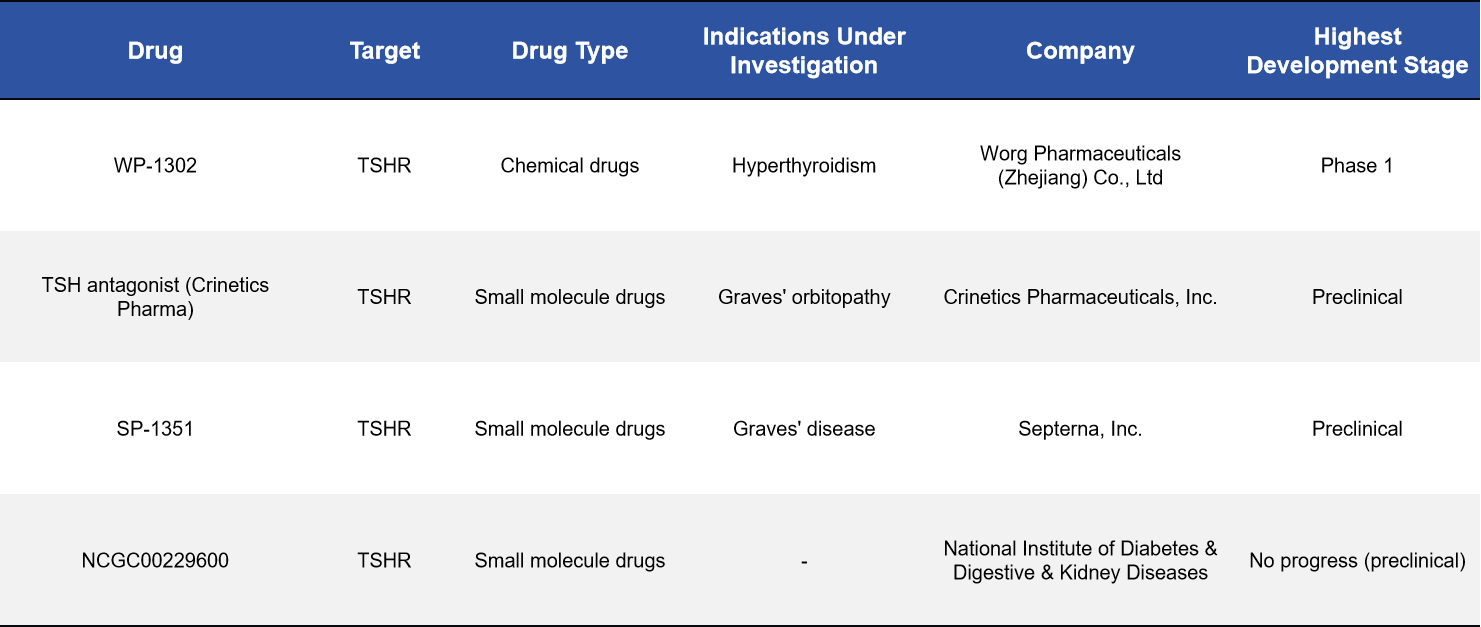

Several candidates have entered clinical or preclinical development, including WP-1302 (Worg Pharmaceuticals, Phase I), SP-1351 (Septerna, preclinical), and a TSHR antagonist developed by Crinetics (preclinical). These compounds have the potential to offer Graves’ disease patients more precise, mechanism-based alternatives to conventional antithyroid therapies.

2.3 Monoclonal and Bispecific Antibodies: More Refined Control of Disease-Relevant Signaling

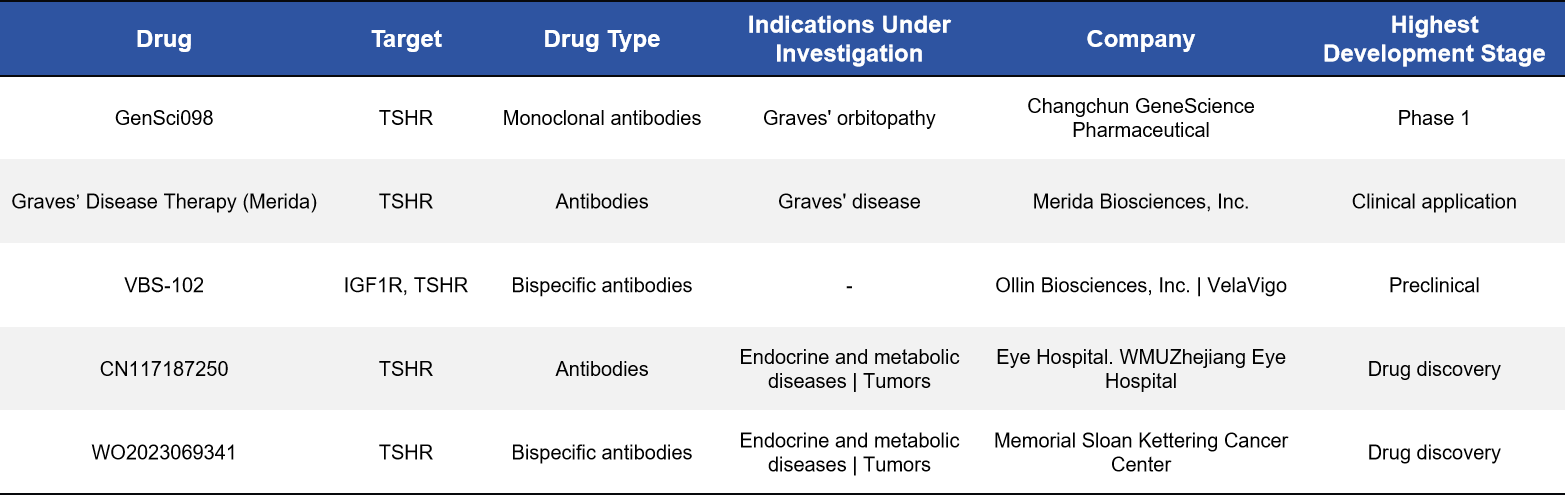

Antibody-based therapeutics enable highly specific recognition and modulation of TSHR activation and represent another rapidly advancing strategy. For example, GenSci098, a monoclonal antibody targeting TSHR, has entered Phase I clinical trials. In parallel, VBS-102, a bispecific antibody targeting both TSHR and IGF-1R, is currently in preclinical development.

The emergence of bispecific antibody strategies enables simultaneous modulation of two signaling pathways closely linked to disease pathogenesis, offering a more comprehensive intervention for complex disorders—particularly thyroid eye disease.

2.4 CAR-T Cell Therapy: A Frontier Approach for Thyroid Cancer

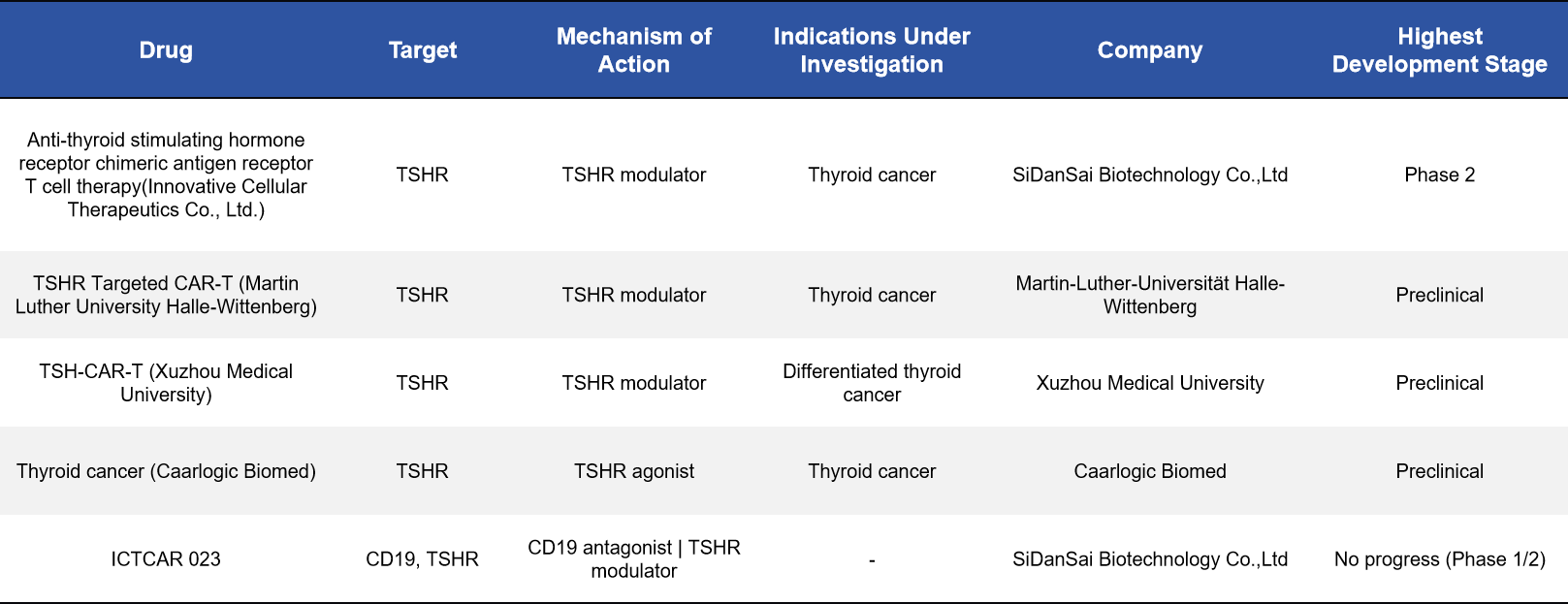

TSHR is highly expressed on certain thyroid tumor cells, making it an attractive target for CAR-T cell therapy. Several TSHR-directed CAR-T programs have progressed into clinical or preclinical development. Among them, anti-TSHR CAR-T therapy developed by SiDanSai Biotechnology has advanced to Phase II clinical trials, representing the most advanced TSHR-based cell therapy program to date.

In addition, academic institutions such as Martin Luther University and Xuzhou Medical University are actively exploring related approaches. These therapies are primarily intended for thyroid cancers that respond poorly to conventional treatments and may provide entirely new therapeutic options for affected patients.

2.5 LYTAC-Based Degraders: A Novel Mechanism to Reduce Receptor Abundance at the Source

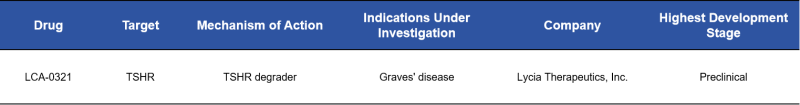

LYTAC (lysosome-targeting chimera) technology is an emerging drug design strategy that enables direct degradation of cell-surface target proteins, rather than merely inhibiting their function. LCA-0321 (Lycia Therapeutics) is among the few publicly disclosed TSHR degraders and is being explored for the treatment of diseases characterized by excessive receptor activity, such as Graves’ disease.

This approach holds promise for achieving stronger and more durable therapeutic effects by reducing TSHR abundance at the protein level.

2.6 Imaging Probes: Enhancing Precision Diagnosis of Thyroid Cancer

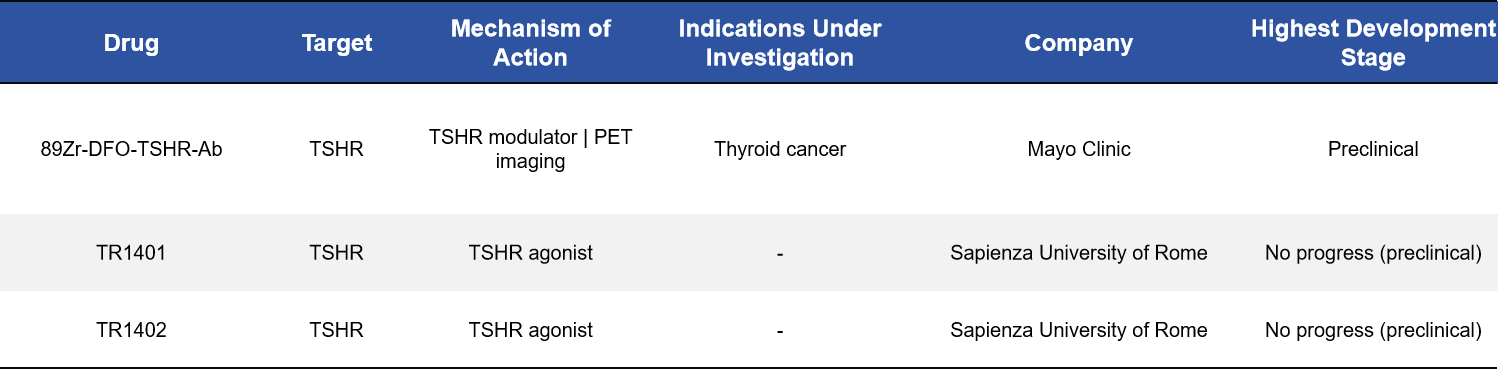

Beyond therapeutic applications, TSHR is also being developed as a target for molecular imaging. Radiotracers such as ⁸⁹Zr-DFO-TSHR antibodies and TR1401/1402 have been evaluated for PET imaging, enabling more accurate identification of thyroid cancer lesions and providing refined guidance for surgical or radiotherapeutic interventions.

3. Why TSHR Is a Target of Exceptional Strategic Value

Taken together, TSHR is far more than a classical receptor involved in thyroid function regulation. Instead, it represents a highly versatile therapeutic target with multiple dimensions of drug development value:

Autoimmune diseases: In Graves’ disease, thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibodies (TSAb) are the primary pathogenic drivers. Therapeutic antibodies or antagonists targeting TSHR can directly neutralize or block receptor activity, representing the most direct and mechanistically well-defined treatment approach.

Tissue-specific pathology: TSHR is expressed in orbital fibroblasts and actively participates in the pathological remodeling observed in Graves’ ophthalmopathy (GO). Accordingly, tissue-focused inhibitory strategies—such as small molecules or antibodies—offer the potential to selectively treat GO with targeted precision.

Metabolic–immune crosstalk: The TSHR–CypD signaling axis provides a novel molecular mechanism linking TSHR to metabolic disorders, including insulin resistance. This insight extends TSHR beyond its traditional role in thyroid disease into the emerging field of immunometabolic disorders.

Oncology: In thyroid cancers—particularly radioiodine-refractory subtypes—TSHR expression and downstream signaling may offer actionable therapeutic entry points. TSHR-directed CAR-T cell therapies and targeted agents represent promising future directions in this setting.

Robust structural foundation: Advances in structural biology, including cryo-electron microscopy structures of the TSH–TSHR–Gs complex, the activated state induced by the M22 antibody, and the inhibited state stabilized by the K1-70 antibody, have provided deep mechanistic insights into TSHR activation and inhibition. These data constitute a strong structural framework for rational drug design.

Favorable safety potential: Compared with conventional thyroid treatments—such as antithyroid drugs or radioactive iodine—direct modulation of TSHR activity may offer improved controllability of adverse effects. For example, the TSHR-blocking antibody K1-70™ has demonstrated a favorable safety profile in Phase I clinical studies.

In summary, from unmet clinical needs and mechanistic clarity to structural understanding and development feasibility, TSHR stands out as a highly promising and multidimensionally exploitable therapeutic target, with substantial potential to reshape future strategies for thyroid and related diseases.

4. DIMA BIOTECH Solutions: Full-Length TSHR Nanodisc Protein

In the development of TSHR-targeted therapeutics, a wide range of intervention strategies—including small molecules, antibodies, and peptides—are actively being explored. However, all of these approaches critically depend on access to receptor proteins that retain native conformation and functional activity. As a canonical G protein–coupled receptor (GPCR) with a highly complex transmembrane architecture, full-length TSHR is notoriously difficult to express and stabilize in vitro using conventional expression systems. The inability to maintain its native structure and signaling competence has long constrained studies of ligand binding, signal transduction mechanisms, and drug screening.

Accordingly, full-length TSHR membrane proteins presented in a native-like lipid environment, such as nanodiscs, have become indispensable experimental tools for receptor pharmacology, antibody recognition, and molecular screening. Leveraging its established Nanodisc membrane protein platform, DIMA BIOTECH has successfully produced full-length TSHR proteins with intact transmembrane domains and native conformational integrity.

This TSHR Nanodisc protein remains stable in a detergent-free environment and is well suited for high-quality studies of ligand binding, signaling mechanisms, antibody epitope mapping, and drug screening. By preserving the biological relevance of the receptor, DIMA’s solution enables more reliable and translatable data generation, thereby accelerating research and development efforts centered on the TSHR target.

Human TSHR full length protein-synthetic nanodisc(FLP120045)

In addition, we offer custom biotinylation services to support a wide range of streptavidin-based applications, including detection, capture, and functional assays. This service facilitates rapid execution of drug screening and mechanistic studies.

- TSHR-Related Product

|

Product Type |

Conjugate |

Cat.No. |

Product Name |

|

Recombinant Protein |

Unconjugated |

PME101523 |

|

|

Full Length Transmembrane Proteins |

Unconjugated |

FLP100045 |

|

|

Unconjugated |

FLP120045 |

||

|

Monoclonal antibodies |

Unconjugated |

DMC101228 |

|

|

Biotinylated |

DMC101228B |

||

|

Biosimilar reference antibodies |

Unconjugated |

BME100079 |

|

|

Unconjugated |

BME100080 |

||

|

Biotinylated |

BME100079B |

||

|

Biotinylated |

BME100080B |

||

|

PE-conjugated |

BME100079P |

||

|

PE-conjugated |

BME100080P |

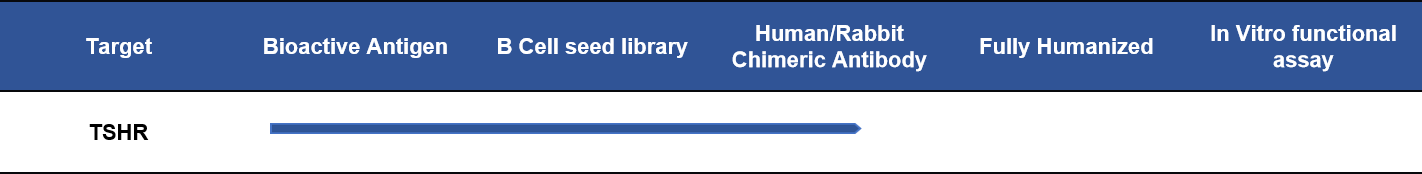

- TSHR Lead Molecule Development Progress

References

- Zhang Y, et al. Targeting Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone Receptor: A Perspective on Small-Molecule Modulators and Their Therapeutic Potential. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2024;67(18):16018-16034.

- Davies TF, et al. TSH receptor function and signaling: implications for Graves’ disease and thyroid eye disease. Endocrine Reviews / Autoimmunity reviews / Front Endocrinol.

- Sanders J, et al. Human monoclonal stimulating autoantibody M22 and its interaction with the TSH receptor. PNAS / J Biol Chem.

- Furmaniak J, et al. The blocking TSH receptor antibody K1-70 and its therapeutic potential. Clin Endocrinol / Thyroid.

- Jiang X, et al. Cryo-EM structure of the human TSH receptor in complex with stimulating autoantibody or ligand. Nature / Nature Communications.

- Kleinau G, et al. Comparative modelling and molecular dynamics of TSHR activation mechanisms. Autoimmunity Highlights.

- Krieger CC, et al. Structural and functional interaction of IGF-1R with TSHR in thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. Endocrinology.

- Smith TJ, et al. Pathogenesis of thyroid eye disease: TSHR and IGF-1R crosstalk. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

- Morshed SA, et al. Non-stimulating TSH receptor antibodies induce cellular stress and inflammation. Thyroid / Endocrinology.